IRAN ART EXHIBITION: TILE WORKING IN IRAN FROM THE PAST UNTIL NOW

The origin of tile production is the art of pottery, which is one of the most ancient human arts. The first works of this art in Iran date back to about 10,000 BC, which is not baked in the form of flowers, and the works of the first pottery kilns date back to about 6000 BC.

Continued progress in the pottery industry has led to changes in production methods, including the change of kilns, the invention of the potter’s wheel, and the quality of pottery materials such as painting and glazing. The beginning of glazing, which made it possible to waterproof, as well as to paint, beautify pottery and tiles, and to prepare tiles, dates back to about 5,000 years ago.

Tile history

The earliest forms of tiles date back to prehistoric times, when the use of clay as a building material was developed in several early civilizations. Early modern tiles were roughly shaped and did not have the durability of today’s tiles. Tile materials were extracted from riverbeds, formed into building blocks, and dried in the sun. Early tiles were raw, but even 6,000 years ago, people used them to decorate tiles using fine painting and engraving.

The evolution of tiles from the past to the present

1 – Baked tiles (Firing Tile)

The ancient Egyptians were the first to discover that clay tiles baked in a kiln were stronger and more water resistant. Many ancient civilizations used small baked square clay tiles for architectural decoration. The buildings of the ancient cities of Mesopotamia were painted with unglazed red pottery and colorful tiles.

2 – Glazing Tiles

Iranian tiles were influenced by tiles imported from China. These tiles, which were used for decorative purposes, spread throughout South Asia, North Africa, Spain and even Europe. Because Islamic art originated in the human imagination and influenced the development of Islam, artisans turned to brightly colored tiles or intricate textures.

IRAN ART EXHIBITION: Bold glazed tiles were stacked together in large mosaic patterns and subtle color changes. Muslim craftsmen used metal oxides such as tin, copper, cobalt, magnesium, and antimony to glaze the tiles, resulting in a brighter, stronger glaze.

In the 15th century, metal oxide glazed tiles became popular in Italy and gradually penetrated among artisans in northern Italy. Major European trade centers paid attention to these local motifs, so that some of these tiles are still in use, such as Delft tiles (from Delft in the Netherlands) and Magulica tiles (from Mallorca in Spain).

3 – Modern Tiles

Today, most commercial manufacturers use the Press Dust method. The mixture is first pressed into the desired shape and then glazed (it may not be glazed as well) and then baked in the oven. Some artisans may produce tiles in the desired shape by pressing a mortar or flattening the dough and cutting it using molds such as confectioners.

Whatever the method of cutting the tile, it needs to be baked to make it hard. The purity of the clay, the frequency of baking and the temperature of the oven are factors that affect the price and quality of the tile. The furnace temperature varies from 900 to 2500 degrees Fahrenheit. The lower the oven temperature, the higher the porosity of the tile and the softer the glaze. Higher temperatures produce denser tiles and stronger glazes.

IRAN ART EXHIBITION: The edifice used to belong to Mohammad Taqi Khan Ehtesabolmolk, one of the members of the royal family of the time in the Qajar Dynasty.

Ehtesabolmolk had two sons, Hassan and Mohsen, who went to Europe to continue their studies.

Hassan was into literary, political and social activities and died young. He left behind a very well-known play titled “Jafar Khan Back Home from Europe.”

In 1939, Mohsen returned home after finishing his studies in the fields of Drawing, History of Art and Archaeology, and began to live in his father’s home, the current Moqaddam Museum, along with his French wife.

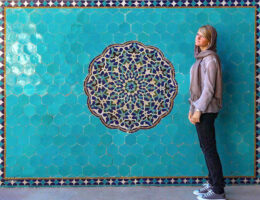

In addition to their scientific activities, the couple began to collect Iranian antiquities and cultural items. Moqaddam artistically fitted into the mansion many of the invaluable items that he collected, including tiles and cut stones, inspired by traditional and historical architecture. That is why the edifice has turned into a treasure trove of Iranian tilework.

The tilework at this mansion is a brilliant example of Iranian visual culture which is based on Persian classic literature, including “The Book of the Kings,” the magnum opus of renowned 10th-century Persian poet Ferdowsi.