IRAN ART EXHIBITION: SHOW OFF OF TILE WORKS IN PERSIAN GARDENS

Beauty and artistry can be seen everywhere in Iran, and its philosophy and religious beliefs are reflected in the country’s public and private spaces. In this article we will look specifically at the history of the country’s famous garden design and mosaic tile work.

The Persian Garden

Water plays a central role in the gardens of Persia (modern-day Iran), and it is reflected in the chahar bagh (“fourfold garden”), a model of garden philosophy and design used as a blueprint for landscaping throughout the Arab world and former Moorish territories in Asia and Europe. This is evident in India’s Taj Mahal in Agra and Spain’s Alhambra in Andalusia.

The chahar bagh has its roots in the 6th Century

The chahar bagh has its roots in the 6th Century palace gardens of the Achaemenid kings of the Achaemenid Empire (also called the First Persian Empire). The gardens of Cyrus the Great, located in the ancient dynastic capital of Pasargadae (near modern-day Shiraz in Iran) share the same layout: they have a source of water in the centre (such as a fountain) that flows into four narrow canals, running at right angles and dividing the garden into four beds. The gardens are also marked with a walled enclosure, providing shade and a respite from the hot weather.

Zoroastrianism was the religion of the empire

Zoroastrianism was the religion of the empire, and this form symbolizes the Zoroastrian division of the universe into four elements: earth, water, wind, and fire.

Persia itself was imagined by its people as a garden, and during the Sasanian period (224-651 AD), Persians erected walls around their territory to protect the land from the nomadic Huns and the Bedouin Arabs.

The invaders still came. The Muslim conquest of Persia in 651 AD led to the decline of the Zoroastrian religion, but the fourfold form persisted as it also had a resonance with Islam, symbolizing the four rivers of life described in the Quran. In fact, the word “paradise” derives from the ancient Persian word pairidaēza (“walled around”), which was used to describe the gardens, walled and separated from their surroundings. “Paradise” is symbolically referred to as “Jannah” in the Quran, an Arabic word which means “garden”.

UNESCO added the Persian garden to its list of World Heritage Sites in June 2011, citing its “perfect design”, innovative engineering and architecture, and sophisticated water management. “Persian Garden” is UNESCO’s collective name for the nine gardens from various Iranian provinces, including the ancient gardens of Pasargadae, included in the list.

The other UNESCO-protected sites that travellers can visit include:

Eram Gardens (Bagh-e Eram)

IRAN ART EXHIBITION: The Eram Gardens are now located within the Shiraz Botanical Garden (established in 1983) of Shiraz University. Historical evidence suggests that the gardens date back to the 11th century, built during the reign of the Seljuk Dynasty. Restored by the Zand Dynasty (1750-1794), it was later acquired by a Qashgai tribal chief, Mohammad Qoli Khan. A three-story pavilion, which still stands in the gardens today, was added by Mirza Hassan Ali Khan Nasir-al Mulk, who bought Eram from the Qashgai tribes. The gardens have more than 45 plant species, 300 rose species, towering cypress trees, and fruit trees such as pomegranates, sour oranges, persimmons, olives, and walnuts. The pavilion itself, with beautiful tiled ceilings, is an architectural wonder.

Fin Garden (Bagh-e Fin)

The 16th Century Fin Garden is located in the suburb of Fin outside Kashan, a lush oasis surrounded by an arid desert landscape. It is famous—and infamous—for being the site of exile of prime minister Amir Kabir, whose progressive reforms earned the ire of the Persian royal family. In 1852, Kabir was assassinated (or, according to other accounts, was forced to commit suicide) in one of the garden’s hamman or bathhouses, upon orders of the Shah. Fin Garden has cypress tree-lined avenues, flowers such as jasmine, violets, tulips, and narcissus, and varieties of fruit trees including apple, orange, and cherry trees.

Dolat Abad Garden (Bagh-e Dolat)

The Dolat Abad Garden dates back to the 12th Century, commissioned by Mohammad Taghi Khan-e Bafghi during the Zand dynasty as his residence. The garden has a vineyard as well as pine, cedar, grape, cypress, and pomegranate trees. The garden is famous for having Iran’s tallest badgir, or wind catcher, a forerunner of the modern air-conditioning system and which was traditionally used by Persian homes to keep cool in the desert. Dolat Abad’s wind catcher stands at 34 meters, reconstructed after its collapse in the 1960s.

Persian Mosaic Guides

The Persian garden represents the aesthetic and practical aspects of Iranian design, and this is also evident in the creation of Persian tiles. Tiles were used for two primary reasons: to weatherproof clay bricks which would otherwise erode in the extreme conditions of the desert, and to ornament buildings.

Tile decoration has been used in Iran for millennia. The earliest examples of mosaic patterns are attributed to the second half of the 2nd millennium BCE in Mesopotamia, when artisans used coloured stones to create geometric patterns on temple columns at Ubaid.

Tile decoration evolved from simple stones to actual fired and glazed brick during the Achaemenid Empire, as can be seen in the palace at Susa and the buildings in Persepolis.

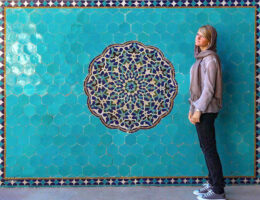

During the Islamic period of Iran, tiles were used to decorate mosques, leading to breathtaking and mesmerising wall and ceiling designs. Turquoise became a popular colour for glazed tiles starting in the 10th century.

Artisans began using the Moraq tiles (mosaic style) technique at the end of the Ilkhanid period (13th century), in which tile panels were created by cutting tiles of various colours based on a pattern, piecing the tiles together using liquid plaster as glue, and applying the whole hardened panel on the wall.

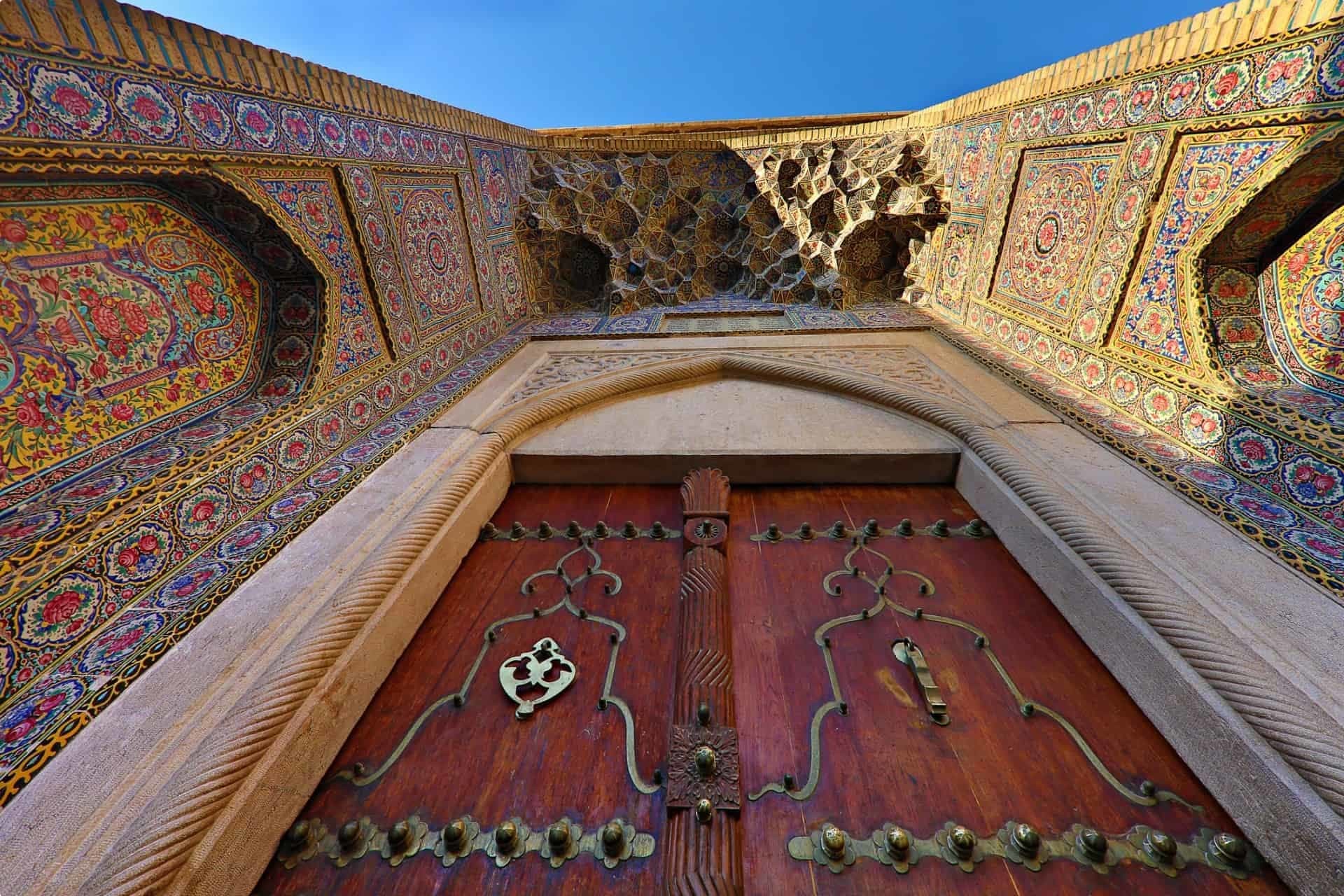

IRAN ART EXHIBITION: One edifice that is considered an architectural masterpiece and a treasure of Islamic architecture is the 16th century Shah Mosque (also known as Imam Mosque or the Royal Mosque) located on the Naghsh-i Jahan Square (“Image of the World”, also known as Imam Square) in Isfahan. The Imam Square and the grand mosque are products of the massive urban planning undertaken in 1598, when Shah Abbas I moved the capital of Persia from Qazvin to Isfahan in an effort to avoid assaults by the Ottomans and to control the Persian Gulf.

Both the mosque and the square are listed by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites. The Shah Mosque, famous for its seven-colour mosaic tiles and calligraphic inscriptions, is located on the south side of the square and is angled at 45 degrees to face Mecca.

Standing on the eastern side of the square is the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, which has no minaret or tower from which the faithful are called to prayer, as this mosque was built for the private use of the Shah and his family.

Detail inside Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque

Another UNESCO-listed mosque in Isfahan is Masjed-e Jāme (“Friday Mosque”) or Jameh Mosque, which was built and renovated continually for twelve centuries, starting in 841. This congregational mosque is the first Islamic building to adapt the four-courtyard layout of Sasanian palaces to Islamic religious architecture, and served as a prime example for mosques that were built after its construction. The Jameh Mosque is still used for prayers.

Located on the west side of Imam Square, on the opposite side of the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, is the Ali Qapu Palace built at the tail-end of the 16th century as a residence of Shah Abbas I. This imposing structure, intended as an entrance (ali=”great”; qapu =”gate”) to Persia’s complex of palaces, is 48 metres high and has six storeys connected by a spiral staircase. Its interior is filled with frescoes, paintings, and sophisticated tile work. The third floor opens out to a hall where the Shah entertained his guests.

While in Isfahan, travellers may want to take a carriage ride around the square, which is one of the largest public squares in the world. They can also drop in on tile maker shops and have a chat with the shop owners, who more than likely are members of families who have been in the tile making business for six or more generations.

IRAN ART EXHIBITION: The 19th century Nasir al-Mulk Mosque in Shiraz, Fars Province is also known as the “Pink Mosque” because of its rose-coloured tiles. Built to catch the morning sun, the Pink Mosque is best appreciated in the morning when sunlight shines through its stained-glass windows, turning its interior into a kaleidoscope.

Mosaic tiles are not exclusive to Iran’s mosques. One of the finest examples of the use of this technique on a Christian structure is the Vank Cathedral (also known as the Holy Saviour Cathedral, or the Church of the Saintly Sisters) in the New Julfa district of Isfahan. The district is named after the city of Julfa in Armenia (today’s Azerbaijan Republic) and “Vank” is an Armenian word meaning “monastery”. The cathedral was established in 1606 and completed in 1664 for the hundreds of thousands of Armenians who were deported during the Ottoman War (1603 to 1618) and were resettled by Shah Abbas I in the district.

The cathedral’s interior is an interesting mix of Christian and Islamic design, with Italian and Dutch-style frescoes on the walls and Persian-style gold-and-blue mosaic tiles on the walls and ceiling. The cathedral is topped with a dome, at first glance making it look more like a mosque than a Christian church.